What will mend the cracks?

Jul 06, 2022

I am a naturally optimistic person. I have a spirit of hope inside me that still believes we can change prevailing storylines and create a human society that works for all. And at the same time, I am confronted with the very real challenges all around us, challenges that have their basis in some of our most treasured mythology.

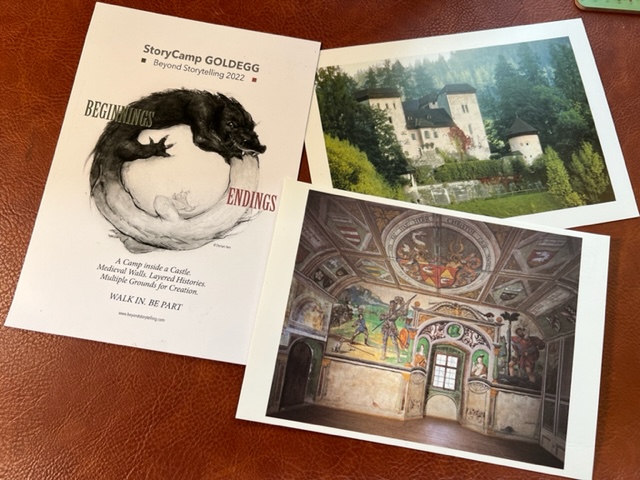

In Europe last month I attended the Beyond Storytelling Camp, grateful to be in a circle of 50+ practitioners from around the world. We met in the tiny Austrian town of Goldegg, just south of Salzburg. Our meeting place was a small castle replete with an historical treasure trove of painted art.

Every surface displayed allegorical images and the shields of important people and places. The Knights Hall was so full of story, in fact, that it was overwhelming. Every woman present noticed the weight of it immediately. It was a clear and concise picture of male power captured in 1536.

Sitting in this room was a stark reminder both of the power of place (and how the stories it holds from the past are still alive) and how history continues to ripple through the present. The painting of the story of David and Goliath, for example (have a look at the postcard lower right), is actually a depiction of an Ottoman soldier and a veiled wish that they would finally be defeated. The Ottoman Empire laid siege to Vienna in 1529 and their final retreat was only in 1913.

Two things to point out that still exist today as ripples out from this story. The first, humourously, is the croissant, which was invented as a symbol of victory over the Turks and now seems to be simply a buttery flaky treat everyone consumes without knowing its history. The second, more seriously, is the prevailing and often derogatory feeling about Turkish people in Europe, even though they were invited to support the reconstruction of the continent after World War II. "Gastarbeiter" is the word Germans use to describe these people, but what is it like to be a "guest" when there is no real welcome, even generations after your people's arrival?

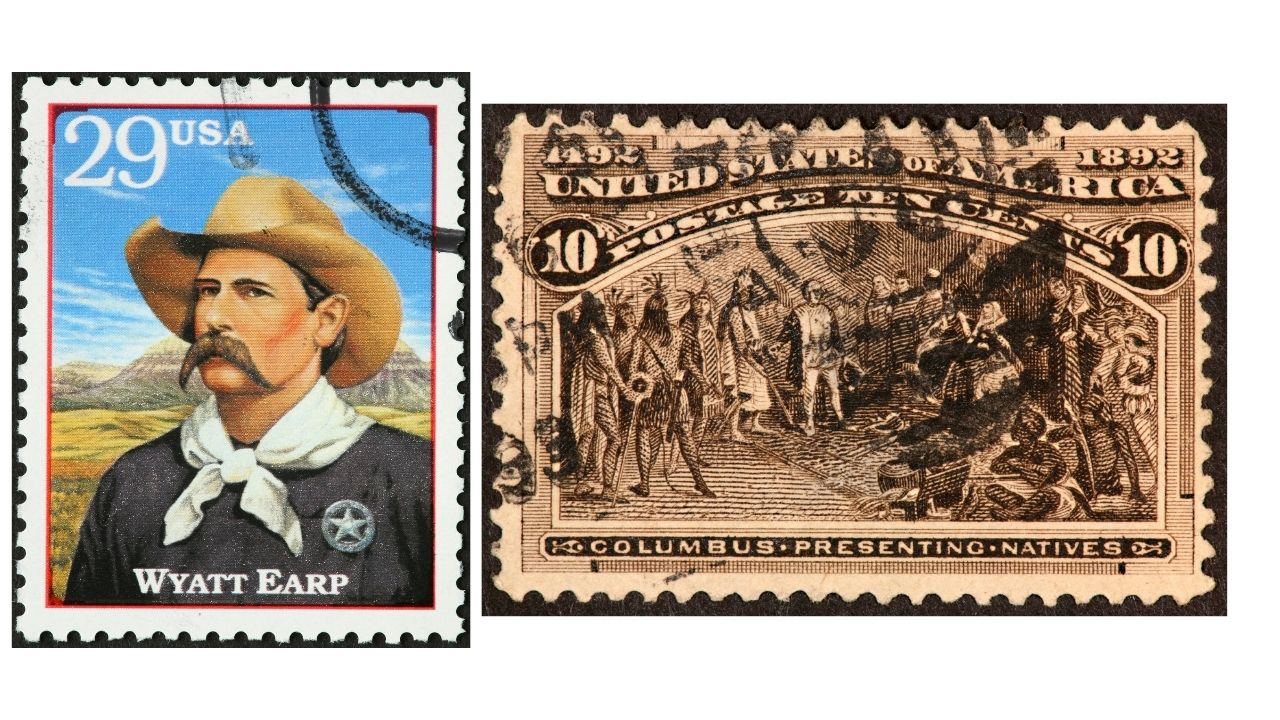

I called a session during Open Space at the Camp called "What comes after the Hero's Journey? Can we move beyond the monomyth?" I will break down our conversation in another post, but I wanted to raise what I consider to be the dangers in the way we are playing with this structure in our storytelling. The rich structure devised by Campbell has been striped of its nuance and used in every aspect of life from movies to politics to branding and personal psychology. At the same time it follows a very masculine structure and is often used to support an individual focus, as well as to define what we consider "heroic".

Perhaps the most dangerous of these takes on the Hero's Journey is the idea that a good guy with a weapon can defeat the evil challenge, whatever it is. Francisco Canti's guest essay in todays New York Times looks at America's prevailing gun myth in this way. President Bush's statement around 9/11 "You're either for us or against us!" sounded precisely like a direct take from this myth as well as a line from movie about the old West.

I have friends who were face to face with the shooter in the recent Copenhagen shopping mall incident, fearing for their lives. This is a rare occurrence in Denmark, but it begs two questions: What are we prepared to do about the storylines creating a growing wave of younger and younger white men who are committing mass murder? What stories are supporting the export and practice of violence around the world?

Prevailing narratives can be so hard to change specifically because we accept them as the truth. Brett Davidson takes this on in his Stanford Social Innovation Review article "What makes narrative so hard to change?'. In the article he says:

"Narratives are always, always tied to power—and an important first step is to expose that power for what it is. As the Frameworks Institute points out in their publication The Features of Narratives, dominant narratives, those that make the existing social order appear natural and just, embody the perspective and interests of the powerful—but do so while presenting themselves as neutral, without a particular perspective: “They seem to be told from nowhere.” An example is the narrative of meritocracy. This is seemingly neutral—anybody can succeed if they work hard enough—but in fact helps justify the position of the already rich and powerful as fairly earned, while blaming the poor and marginalized for their disadvantaged situation. One of the key steps in narrative change then is to remove that mask of naturalness and neutrality."

Fellow facilitator and host Chris Corrigan paints this in stark relief as a national issue in his recent blog talking about the fearful stories we are still creating that stem out of colonialism, saying: "There is an interesting set of narratives that underpins the populist project in North America. Wedge politics has always been about stoking fear in an unreal other." I heard this very "someone is coming to get you" narrative in 2015 in Prague as the first wave of Syrian refugees began arriving. How differently Europe has responded to the millions of displaced Ukranians.

I often say there is no such thing as an innocent story. Every story wants something. All the way from the fairly innocent "please be in this experience with me!" to "We don't call that war." In every moment we are challenged to be awake to the narrative that is subtly shaping how we see ourselves and experience life.

This great challenges to be awake and act with consciousness points to a key quality in facing times of complexity -- curiosity.

Curiosity gives us the ability to look at things we take for granted and question them. Curiosity enables us to ask why some people are missing or overlooked. Curiosity enables us to combine things in new ways and experiment about the outcome. Curiosity led the small boy in Hans Christian Andersen's story to say out loud: "The King has no clothes!"

As I was returning back to my home country, I was asking myself some pointed questions about where and how I want to live. Do I want to live in a country where there are more guns than people and where the co-created narrative of violence will not be discussed? Do I want to live in a country which has "freedom" as a key value and yet seems to actively work at undermining the rights and freedoms of "those not like us" (however that is defined in the moment)? Do I want to live in a country where I might be bankrupted by visiting the hospital?

All of these conditions of life in this country are based on accepted narratives. They are also based on a societal story about the autonomy and merit of individualism and the perceived overriding value of personal responsibility. It feels to me that this system -- and its underlying stories are broken. they no longer serve us, yet we seem determined to hold onto them as fiercely as we can.

So now, what is mine to do?

Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the cracks wth gold. A piece mended like this is honoured and valued. So what would it look like to attend to the cracks in human society in such a way? What stories could be our gold, mending the broken pieces and bringing something back into wholeness, something that would be both beautiful and useful?

I am curious to find out.

Isn't it time to have a brilliant ally on your side?

Subscribe to my newsletter for the latest about the power & practice of story.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.